When the world changed

An oral history of the pandemic year at the School of Pharmacy.

When did you first realize the world had changed?

Guizhi “Julian” Zhu, Ph.D., assistant professor, Department of Pharmaceutics: I am from China, actually from the same province where SARS-COV-2 was first identified. And sometime in the end of January, beginning of February, our home province — the whole country — was panicking.

We have Chinese New Year. It's pretty much like Christmas in the Western world. People go to visit friends, family, relatives; a very happy time. This was perhaps the first time that people had to stay at home. No walking out of the home, no interacting with others. I have high school classmates who had to work in the hospitals in the affected cities. That’s when I knew that this was something that's going to be impacting us a lot, when I first realized this is really something going to be very serious.

Serena Bonasera, Ph.D. candidate and research assistant: My family back in Italy was already living the beginning of what was going to be a lockdown, massive lockdown. So I didn't understand as fast as Chinese people, but I think faster than some people living in U.S.

[Here], we were coming to school, we were working. I was seriously concerned. My parents were telling me that things are not going OK in Italy. Restaurants were closing, groceries were closing, everything was shutting down. So that's the moment. I think it was end of February. I had not seen my family since December 2019. I never left my family before coming to U.S., so it's too much for me. I'm just hoping this will finish soon and I can go back home for some time.

Joseph T. DiPiro, Pharm.D., dean and Archie O. McCalley chair: There was so much uncertainty. We couldn't fully appreciate all that was coming down the road. I remember at one point in a meeting with our leaders I said something like, "It looks like we're going to be closed down for a couple of weeks, so we've got to prepare for that. Think about how we would offer our courses. If things really get bad, this could go on for a couple more months. We've got to be ready." Clearly it exceeded all estimations of the duration of what we were dealing with.

Rucha Bond, Pharm.D., associate dean, experiential education: At the end of February of 2020 we were starting to see sites starting to cancel rotations left and right. I had been recently to the interim AACP meeting where we were largely unaffected. Within a week, my role at the school was very affected. We were starting to wonder how we were going to graduate the Class of 2020.

I was terrified for the students. What was going to happen to them? Experiential is the last step before graduation. But that was the time when we were hearing things like, "Oh, it'll be two weeks. Oh, it'll be three weeks." And so I kept thinking, that’s OK. If we can get this class through then it will be better. Surely by then everything will be fine.

Laure Ray, laboratory/research assistant, Bioanalytical Laboratory: When VCU closed down and they actually closed our lab — that was just something that I never thought I'd see happen. It's not something you'll ever forget.

It was pretty scary. I have two kids. They both got out on March 13th. I've got this random picture: I had sent my daughters to school with hand sanitizer. I got this photo as my daughter was leaving school and she's like, "I've got my hand sanitizer." That's her last day of school picture. And it's March 13th. Friday the 13th. Of course.

Lauren Caldas, Pharm.D., associate professor: I watch a lot of zombie-apocalypse shows, and it felt like that. When things started to close is where you really saw it, where it mirrored what we saw with some of these zombie apocalypse shows — you see one event happening, and people saying it's not going to be a big deal, and other people saying it is, both sides of the extreme. But then you start to see things change and close.

Avian Goldsmith, human resources administrator: It was a Monday around the middle of March. An employee came in my office: "I do not want to come to work. I'm not comfortable being here. I just want to leave." You know me, I'm staying in HR policy. There's no guidance given down by the school. I said, "Well, leadership, we're reviewing. We'll let you know."

Then I got 10 more emails: "I'm not comfortable coming to work." I'm thinking, what is this? I've never been through this. I don't know what to do with this. I'm confused, HR-wise. I don't know what to tell my employees. Leadership really doesn’t know what to say. I started to feel so helpless. I didn't know what to do, and I knew this was way bigger than I could even fathom.

Michael Hindle, Ph.D., director, Hindle Research Group, Peter R. Byron professor: March the 16th was a Monday, and I was due to give a lecture. By then students weren't allowed to come to the lecture hall. I gave a lecture to an empty room, which was definitely interesting. I don't think I've ever done that to an empty auditorium. I remember walking out afterwards and I talked to the security guy and I told him it was my first lecture to an empty room. He said, "Oh, you should've told me. I would have come down and listened."

K.C. Ogbonna, Pharm.D., associate dean of admissions and student services: At the time, all of the communications from the university and all the conversations we were having internally here at the school were all in preparation for a few weeks or even up to a month that we would be in a hybrid or predominantly virtual environment. At the time it was about figuring out what we need to do in the next weeks to a few months and how we are going to adapt the clinical training to make sure those students are well cared for.

Rucha Bond: All of a sudden, left and right, hospitals were saying, "We can't take students. We're preparing for a pandemic, can't take students." Our community pharmacies did OK for a little while, but even they started saying, "We can't take students."

I got into this pattern where I would check my email, eat dinner, basically go back to work. And then I’d wake up at 2 or 3 a.m. to check my email again, just so I wouldn't wake up to the barrage because overnight we would have, I don't even know how many cancellations.

Then students are freaked out, right? They're so close to graduation. We were trying to find places to put them. What could we do? We were so close though to them finishing that it was difficult. We wanted to figure out a way to get them to finish. At that point in time, we were still under the impression that it would just be a few months.

K.C. Ogbonna: When we pulled students from clinical rotations I knew it was bigger than anything we had ever envisioned. Nearly all of our clinical partners across health systems, not isolated to one health system. They said, "Your students cannot continue in this clinical environment right now." That to me was a very defining moment: Our trainees who are supposed to be on the front lines, they thought they were too much at risk to continue. That was the defining moment.

Michael Hindle: March 10th to March 20th, we got into lockdown. Those 10 days were fairly hectic. All the equipment had to be shut down. I was telling students to take the lab books home, take whatever materials that they need in order to continue projects that they could write up. My thought was that they can use this time to write up projects, to write papers.

In that chaos of that first week, we were basically closing down pieces of equipment. Experiments that needed to carry on, we would make arrangements so that someone would come in and carry on those arrangements. But for the most part, we closed down. We shut down everything that we had active.

Rucha Bond: I was pulling 16-hour days regularly, 24/7. That was something that affected the whole experiential office, because cancellations would occur at any time and so we’re pretty much working around the clock. As soon as a site would be lost, we'd have five students who'd received an email saying, "You can no longer come on rotation here." So we immediately had five student emails plus the emails from the preceptor, plus the thought of, What am I going to do? Where am I going to finish? What can we do? And it was just — it was just constant.

Michael Hindle: A lot of graduate students, I think it was really tough for them. A majority are from overseas. They’re thrown into this big world where the one piece of contact that they have is coming to work every day, or coming to school every day. And then that's just taken away.

Serena Bonasera: One of my worst fears when I came for Ph.D. on the other side of the world was if something happens and I cannot go back home. And I never, ever thought in my life a pandemic could happen. It's not something you think about. You think about a war, but not a pandemic. I said, "OK, if it's if it's a war they will just bring me back to my country somehow." But a pandemic, it's like nothing is really happening in the sense that you're not in a danger that is dependent on other people. It's depending on you. You have to stay home — simple. But then, when you live so far, it's more complicated.

Camille Schrier, Pharm.D. student and Miss America 2020: I had a booking manager when I was Miss America. She put everything on my calendar in red; she scheduled everything and I just went with what it was. I probably did 200 events, more than that, throughout my process as Miss America.

That Google calendar started to clear — all of the clients I was working with were rescheduling or canceling events. I watched all the red clear off for weeks and weeks and weeks and then all the way through until August or September.

I was like, OK, maybe this is a bigger deal. People were worried and my entire professional life was changing very quickly. I'm like: This is a big deal. The world is changing.

Watching those events move off my calendar, going from completely full, every day being red, to every day being nothing — that was probably the moment I said, "This is going to be a really different year than what I ever expected." I remember landing home on March 13th of last year and I didn't leave until July.

Scott Crenshaw, building manager: When did it feel real? It’s very clear. The moment when I taped a sign on the front door of the Smith Building that we were going to be closed indefinitely until further notice. March the 21st. I took a picture of it and just kind of walked off. I was just shaking my head: Wow. This is real.

Lauren Caldas: We all thought, "We get this long spring break. It's going to be great. We're going to hang out. We're going to paint and bake bread." And then it just didn't stop for an entire year. And everything bad happened in that year.

What was the shutdown like at first?

Joseph T. DiPiro: We had to keep readjusting. There was a point there when so many aspects of what we were doing were changing almost daily. It could be the safety measures that we were putting in place. It could be how we were offering courses, what we were doing in research labs. Really every aspect of it. It was figuring all this out while people were home and changing on almost a daily basis.

K.C. Ogbonna: It felt strange and uncertain. I remember thinking critically about safety from a student and faculty perspective — what the things are we should engage in versus those things we shouldn't engage in. There wasn't a ton of information at the time. Uncertainty. There just wasn't a lot known at that point.

Joseph T. DiPiro: There was such a need and a call for information and direction. At times it seemed like leaders of the school, leaders of the university, could not provide enough information. It was natural for people to want clarity. What's going to happen? When's it going to happen?

I felt better about it when we knew, OK, we've got some information. I could bring that back and provide some clarity. There were so many times when we couldn't. I'd have to apologize and say, "We don't know. I wish I knew how this was going to play out. I wish I knew how long it was going to be. I wish I knew all that we were going to have to do."

Michael Hindle: Graduate students, you've got to remember the majority are from overseas. So probably English is not their first language. A lot of them are from the Asian countries. Not everyone is aware of how to order groceries online. Even the most savvy of people, if you've never done it before, and especially if you're in a foreign country, how do you make that work? How do you get the groceries in the building? It was those sort of things that I was, at least in that first few weeks, thinking about. Making sure that the people we connect with were going to be OK, at least from a practical perspective, first of all.

Serena Bonasera: At that time, I was not considered an essential employee, and I think that was right. So I was home. I couldn't come to lab. But I was lucky enough that I had to do my proposal, so I focused all my energy in writing or studying or preparing slides for my proposal.

But I was not happy. Completely not happy. When you're an international and a Ph.D. student, you don't have a lot of money, so you need to live in small places, small apartment. The apartment I used to live in did not have any window facing outside because I did not expect a pandemic coming. So basically, my life was with artificial light most of the time.

I was scared at the beginning. I was very scared of stepping outside my apartment because I didn't know if the people living around me were affected by the virus, to what extent I could get the virus, touching doors or whatever. I was very scared. And so I tried to focus on my proposal.

Guizhi "Julian" Zhu: To me it was mentally and psychologically damaging to read the news. For the first few months every day I would keep refreshing the stats multiple times a day. That was psychologically distracting. I had to even limit my refreshing just to try to stay positive. No one is happy seeing so many families are affected.

Scott Crenshaw: I remember the first time I walked outside, or I think really went somewhere. It was just very strange. Oh my God, I'm outside of my house. I'm going to catch something just from being outside.

K.C. Ogbonna: It was chaotic. Maybe controlled chaos is a better way to describe it. Here I am managing the Admissions and Student Services arm and making sure that recruitment continued. We were continuing to interview students. But also making sure we were doing all of the things we normally do academically. How do we need to change and transition as quickly as possible to a wholly virtual environment?

Katie Shedden, information technology specialist, VCU School of Pharmacy: We had Zoom, we had Kaltura for video management — those were university-supported resources we had access to without an additional cost. We came up with a new way to mesh these two systems that we had access to together to make recording possible. It was not ideal, neither of these systems are meant to do that and software-based lecture capture is still an issue. I hope some product emerges to really handle that.

K.C. Ogbonna: I remember the first few cases of COVID that we had amongst our School of Pharmacy community and how we were going to triage those concerns — weighing the concern for the individual and the privacy for the individual with the concerns of the community at large. Folks were legitimately concerned about who they had come in contact with. How do we allay some of those concerns and provide information that's needed to make decisions for those individuals at the same time while maintaining privacy? I remember that as a moment of how you balance that need for information versus the individual-privacy piece.

The second thing that stuck with me were those students who weren't doing well in the virtual environment. I remember the first few tutor request forms and accommodation forms, and the realization that when you're not in the building and you don't have the ability to see students in the hallway or see students in the lobby and really get a sense that stress is high and anxiety is high. You don't have the same opportunity to intervene. You are reliant on the students to come forward.

Scott Crenshaw: The first two weeks were really kind of a blur to me, just kind of sitting at my desk. You definitely had that sense of isolation in those first few weeks, very much so.

Michael Hindle: We have people living downtown, so I've got postdocs who every night had helicopters flying overhead and hearing all the sounds that are associated with the disquiet and the troubles that were on the streets during the summer, where they don't feel safe to go out. So it's talking to them and trying to reassure them. Not that I could offer any help, other than at least listening. I think the support groups and the emotional side of helping and talking to people came later.

Rucha Bond: Our whole team narrowed down our focus to three main goals for everybody in my office. And one of them was taking care of each other and ourselves and making sure we were all OK and healthy during the pandemic.

Scott Crenshaw: A memory I have is sitting at my desk at home and thinking that pretty much the rest of the world is doing the same thing. And I think that what really made it more real is when I would go online and look at all these vacation cams or city cams of Times Square or Venice. I would look at all them and it would just be just deserted. And it's so weird to see. It's like everywhere is like this. Wow, worldwide, everybody's sitting at home.

Serena Bonasera: I got saved because I got a cat. It was a random thing. I love animals — pets, animals in general — but I could not commit given that I had to go home, or I didn’t know about my future. But then when this happened, I thought, "OK, that's the way you can survive."

So I got this cat, a friend of mine got for me. I had to put a lot of my energies on taking care of her and — I don't know how much you can educate a cat, but somehow educating her. So she helped me. I had someone to take care of that was not only myself, because at that moment it was not very easy. So at least I had her. She saved me and does, not only at that time. She really helped me a lot.

Joseph T. DiPiro: I felt great reassurance from the team that we had working together, both in the school and through the university administration, our senior vice president for health sciences, provost, and others. There were regular meetings. We had opportunity to rely on each other and hear what's going on and get as much of the information as possible. There was kind of a dread because of the uncertainty but also reassurance that we had a really good team that would get through this.

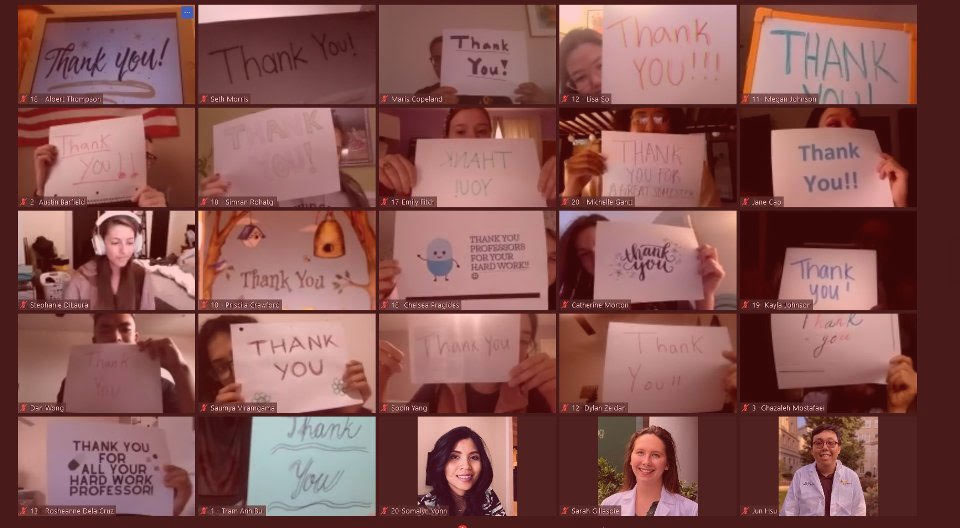

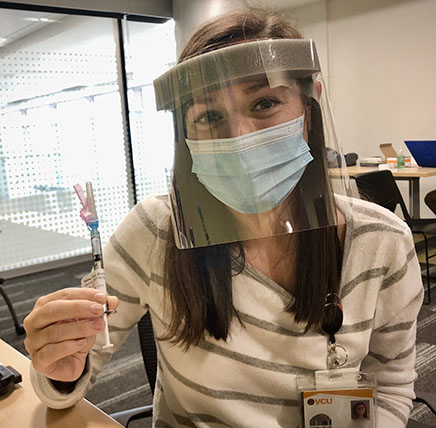

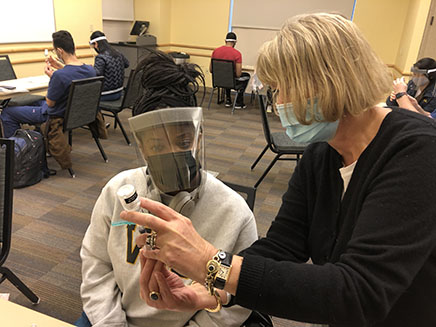

Covid vaccines

Pharm.D. faculty and students administered vaccines at events and clinics across Virginia in the first six months of 2021.

1,500+ Hours volunteered

10,000+ Vaccines administered

How did you find a "new normal"?

Camille Schrier: I would do one or two shooting days a week — I was doing science videos, like that "Cooking Up Science with Miss America" show that I did. The other days in a work week were primarily Zoom days and writing days. Answering emails, doing a lot of nonglamorous work. Sitting at my computer writing shows, coming up with presentations. Because I was still giving a lot of speeches; I was doing them virtually.

It was more of a 9-to-5 — being able to wake up, do this and then just be done for the day and enjoy time with my family. A lot of people ask me if I was disappointed with my experience because of that. A lot of women dream of this Miss America experience where they get to have the glitz and glamor of being on red carpets and all of that. I was actually really happy with how it turned out. I felt like I got to have a normal life and then do some stuff during the day and then just go back and be myself.

Joseph T. DiPiro: We realized how easy it was to run to a meeting [virtually], as opposed to leaving your office, going across campus or to the next building. What could be five minutes to 30 minutes was two mouse clicks and you're at the next meeting. The good of that is being able to have a lot of meetings. The bad is being able to have a lot of meetings back-to-back and not getting up from your desk and getting in those steps and some outside air. That took a good bit of adjusting to.

K.C. Ogbonna: When we were giving the task of who's going to go to the building on given days, I just remember walking through the building and all activity had ceased and stopped. You didn't see anyone. I remember pulling into the parking garage and it’s basically empty and saying, "Wow, this is strange." That stuck with me.

Michael Hindle: I had a group of Pharm.D. mentee students. A few of them used to send me photographs of their walks in the evening, the animals and the flowers that they see. We started to get into an exchange of different animals that we would find on our walks in the evening. We can always find deer, we can always find ducks.

I used to walk a lot around the University of Richmond, nice campus, around the lake. Every time I walked there was a group of three ducks. I used to imagine what that family relationship was between the three ducks. I just couldn't figure it out. There was two guys and a girl, and it was just ... (shrugs, laughs).

Lauren Caldas: My at-home office was a junk room before. I painted a chalkboard in it, put in a green wall. We started to feed the squirrels and name them. We put window feeders for the birds, and the squirrels enjoy them. They ripped down a lot of my screens, but it's been fun. We also got a pandemic puppy. Her name is Waffles.

Laure Ray: I have a 35-, 45-minute commute, so to get an hour and a half of my day back was a really interesting feeling. I started running again because I had all this time now.

Laure Ray: As lab staff, we're used to being on our feet, moving between two labs, three labs. I hardly ever sit down during the day. We sit down for lunch, and that's about it. And now all of a sudden, I have my laptop computer, and I had to figure out how to set up an extra monitor so I wasn't going blind all day. Luckily we had a bunch of administrative stuff that we had squirreled away for a rainy time, a slow point in the lab, that we thought we would get to. So we had a lot to do, which was really something I was very grateful for. We weren't just spinning our wheels. We stayed busy.

What was the most difficult?

Rucha Bond: The hardest thing is clearly the health. Watching our students' loved ones and our staff and our faculty have individuals who did fall ill and even die, that's definitely the hardest part. On a very, very deep level that was a true tragedy.

Katie Shedden: I got married the first week of April when things were really starting to close down. We thought the gate was closing and we weren't going to get our marriage license. But that was actually kind of nice. They knew that we were the only people coming in that day because you had to make an appointment. There were like two people and they were excited that we were coming.

But it was definitely difficult. I wanted to go and see my parents, I wanted to show my mom my dress. That's just one thing that really hit me at the time. My parents, we can't go for dinner, we can't hang out because I'm so scared that I'll make them sick. And I don't know when this is going to be over and I don't know when I can see them. I think that was the biggest fear for me, thinking about access to health care and people in my life that have different risk factors to a disease like this. Seeing how other people are going through that too, with the health of their family members and their children ...

Also, the level of burnout has been really, really pronounced. I've never seen anything like it, I've never felt anything like it myself, like this really weird Groundhog Day feeling. It's a working day or it's not a working day, and that's all it is.

Serena Bonasera: I was terrified about getting the COVID and I was terrified also because I didn't know how much that would cost me. I was very scared that maybe my family at one point needed money because of the situation in Italy. I was terrified. I don't think we have experienced any lockdown compared to what China has done and what some of European countries have done. My parents could not step out of their apartment, period. They still need to have authorization for why they are going out.

Italy is not as good in terms of economy as U.S. I was trying not to spend too much money because if my parents needed, I could send it to them. I was trying to understand, OK, how much do I need if I need to go to the hospital? If my parents get COVID, what do I do? There were international flights only for Italian people that wanted to go back to Italy from U.S., but I was not able to come back to U.S.

I talked about it with Dr. Hindle and I asked him, "What should I do? Should I stay here? Because if this is going to last for two years, staying home, I know I am not able to handle this mentally."

And he told me, "No. No one can handle this, not only you." He helped me a lot. I realized, OK, calm down. I understood the situation: OK, you have to go through this but it's not going to last.

Rucha Bond: I was working with the experiential team, seeing their exhaustion and their fatigue. Wanda talks to a lot of our preceptors and kept trying to recruit, hearing the stories that were coming in. So many of our preceptors were furloughed. Some of them lost their jobs. Some of them could no longer take students.

They were all stories of hardship, whether it's family members’ loss from COVID, coworkers’ loss from COVID, loss of income due to COVID, closing of stores. "I can't afford to stay open." "I have to put my kid through college." We have a preceptor who lost her husband and never even missed a beat taking students. And so hearing those stories was really difficult, and again, they were constant. You just feel such pity.

Avian Goldsmith: I felt helpless. For the first time in my life, I was like, "I need therapy. I need something to deal with this." I'd never felt so confused, so out of control. Then I had to get on the meetings and put the happy face on and give the HR policies.

Leadership, they were doing the best they can with the situation they had, but everything was so gray. Everybody was just trying to figure it out as they go. I didn't want to get up in the morning. I didn't even want to come to work. For a long time I was sad. I was sad, I was lost, I was concerned about my family members. It was just so much.

Laure Ray: All of a sudden it was 24/7 of us and the dogs and the horse. That was a little hard to get used to. The kids were used to having their friends to bounce things off of, and all of a sudden they're having to rely on FaceTime. And the lack of social contact. They canceled prom and my daughter was devastated. They didn't keep up with robotics and that sort of thing. Watching them deal with the disappointments of things just canceling left and right, that was hard. It was hard to sometimes stay positive and keep them moving forward.

Avian Goldsmith: I had a junior in high school who had been told to come home from school. No junior prom, none of that. None of the activities leading up to her senior year. Everything just stopped.

My oldest daughter lived with my parents, and my parents are like 75 and older. I made her come live with me, because at the time she was still going to work. So, I didn't want her to potentially bring it back to my parents. My mom has an underlying lung condition. I took on the responsibility of going to the grocery store for them all the time. Anything they needed, I was like, "No, you're not going out." Just super concerned about my parents. I took that burden on.

Serena Bonasera: I used to video call a lot with my family and with my friends, a lot of hours per day. Around 4 p.m. or so in U.S., they were going to sleep in Italy. That was the bad moment because I knew from that time on up until next morning, I was not going to talk much with anyone. So that was tough. I had, not panic attacks, but I was close.

Avian Goldsmith: People have passed away and I wasn't able to go to funerals. I wasn't able to say bye. I've had death in my family. It wasn't due to COVID, but if we didn't have COVID, this person would have gone to the doctor, but they didn't because of COVID. And within three months they were gone.

This is just an emotional time for me. [Cries.] I'm sorry. I really want to get back with my family again, because there was never ... For the family member who died, there was never really any closure or any of us to get together and grieve together. It was just so quick. So, yeah. My family has been hit very hard.

Laure Ray: I was just so grateful that we had all this administrative work to do but at the same time, part of livelihood is on the samples and the research, and we really started to miss it. It was nice writing grants but at the same time we were ready to start doing the work. It was definitely a lesson in patience.

Camille Schrier: In our professional lives, at least for me, I'm motivated by feeling valued. If I feel valued by the people around me in my workplace or if I feel valued by my clients, when I go out and I'm at an event, people brought me there and they're really happy, that keeps me wanting to do more. The social interaction and being able to see people — when that went away, that was really hard. Which is funny because I'm kind of an introvert.

Laure Ray: We were given essential clearance at the lab because we had some things that were going to go bad if we didn't get back. So we would go back one at a time. We would rotate who would go to the lab to get things at least moving in a direction, so we wouldn't lose any of the samples, or any of the research. I was grateful for that. It was very strange going downtown with nobody there. I had never seen it so empty. I grew up here, so it was eerie.

Scott Crenshaw: After a while I started coming in to the building. There were many times I was here at Smith throughout the day that I wouldn't see anybody. It was very quiet, very quiet. That was weird. I had plenty of quiet time. Plenty. Plenty.

Avian Goldsmith: My youngest daughter kind of felt that I wasn't there anymore. It would be like 7 at night and I was just irritable and I had the computer in front of me, looking at emails.

She said, "Gosh, you never pay any attention to me anymore. Did you even hear what I said? You're going to say that you did but you didn't. You work 24 hours a day."

I was like, "Well, I'm just trying to figure this out."

She's looking at me. "I don't care what you're trying to figure out, but can we have a little normalcy back?"

I was like, "OK, Avian. You've got to make an adjustment. Your relationship with your daughter, yourself, your mental health." That is when I realized I needed to make adjustments.

What helped?

Lauren Caldas: We started playing Dungeons & Dragons. We all get together, a bunch of parents on Zoom, and we play Dungeons & Dragons. We've been doing it for a year and I don't think we'll ever stop. It's a lot of fun. It's creative and silly. It's just something easy to do when the kids go to bed. And no one has to drive or pay for babysitters.

Michael Hindle: I didn't feel isolated. There were always connections, whether it was with graduate students who you would have Zoom meetings with, whether it was mentees, teaching the Pharm.D. class, neighbors, family, friends.

Laure Ray: Without that commute every day I got to spend a little more time with my girls. My oldest goes to Maggie Walker [High School], so she also had a 30-minute commute there and back and schoolwork all night. But now we had a little more time to talk and go through what was going on and absorb the pandemic and the news that was coming to us. So, in a way, my girls and I were really able to hunker down and get through this together.

Avian Goldsmith: One good thing I did learn that I've never done before is pay attention to my mental health. Where I grew up, no one ever talked to me about mental health. There's a stigma in the Black community that we do not pay attention to our mental health. We just truck through it.

I think the most important thing the pandemic did was make me pay attention to my mental health and actually get help for my mental health and treat it just like I would treat my physical body. After this, I made it my point to talk to my daughters and say, "I'm just your mom. I'm human just like you. So I may not be helping you mentally like you need it. If you feel like you need a little extra help or you're like, 'Mom, I'm struggling here,' talk to me about it, and we will get you whatever additional resources, help that you need, because it's nothing wrong with that. There’s nothing wrong with that."

What did you miss?

Joseph T. DiPiro: Seeing the students. It'd just be routine, before COVID, to come into the lobby and there'd be students there and you could chat with them, or students up here on the fifth floor. That all changed.

Lauren Caldas: The energy of the students and my colleagues. That was beautiful.

K.C. Ogbonna: The organic conversations that you wouldn't necessarily schedule a meeting to talk about. That water-cooler chat. In my role, meeting with students is what I do.

Laure Ray: I love working downtown. I love being able to take a walk at lunchtime and see the Capitol, get a bite to eat.

Michael Hindle: Walking into Smith and seeing the students in the lobby. They would always have a word for me, catching me with my pizza or my Chick-fil-A. The ability just to walk through the corridors and chat with people, those random conversation. Walking from the deck, or walking into the building, or running into David Holdford with his cup of coffee.

What lessons will you take with you?

Laure Ray: We're grateful that we all got through this. We know lots of people who lost loved ones and family members and team members. And, our group got through this unscathed, and we're very grateful for that.

If we need something, we can reach out to each other, which is really a testament to the teamwork that we have in the School of Pharmacy. I'd like to say I have learned how to use my computer better, but that would probably not be so true.

K.C. Ogbonna: If it weren't for the pandemic, I'm not sure I would have ever stopped and reflected: Why do I do things that way? When I commute or do other activities, how does that impact everything else? This has given space and reflection, I think, for a lot of folks to think about.

As a school I think we also need to give that some thought. How do students learn best and in what environment, in what ways?

Joseph T. DiPiro: It's not ever something you'd want to go through or want to experience again. We all saw the resilience that people have, in the sense that we can get through it. I thought back often about my parents' generation. My father turned 18 in 1943. People who were in their careers at that time had to put everything on hold. What you planned to do with your life changed. Most men at that time went into the service. Some women went into the service. Some women went into jobs that they didn't expect they would be going into.

I got to speak with elders and how they went through it. They had a sense of resilience: "We rolled up our sleeves and did what we had to do." I got that sense here as well.

Rucha Bond: In a crisis you try innovative things and sometimes they work. One of the big things is preceptor education. It moved all online — we did Zoom education, which has been very well received. That's something we'll continue.

Serena Bonasera: When I was attending webinars or meetings people would ask this question. "What did you learn from this pandemic experience?" Most of them were saying, "My family is important, spending time with them," and so on and so forth. I didn't have to learn that. I already knew.

It's how much working is important for me that I think I learned. I don't know if this is very sad, but I think that's what I learned: I need to go somewhere and meet people to work, in my working environment, or wherever. I can not just be home. That's what I — not learned, but got a stronger feeling of. I need to feel I am useful for something.

I understand that people with different age can have a different perspective. Right now for me, my life is mostly based on working, because Ph.D. is mostly like that. Especially now, during the pandemic, I cannot go vacation, so that's what I'm doing. That's it.

Camille Schrier: I've realized through this that it's impossible to please everyone. And if you try you're going to set yourself up for failure. You're not going to be able to make everybody happy at all times. A lot of us seek that and I know that I seek that often, wanting to please people and make people feel comfortable and happy with what I'm doing. But that's not always your job. That's been one of the biggest lessons that I have learned.

Michael Hindle: It came home to me very quickly that I wasn't suited for sitting around. I feel more aches and pains than I ever felt before. It took some adjustment for someone who's used to being in the lab every day and walking around and barely an hour goes by without me getting out of my office and walking to the lobby to see what's going on, to talk to the students and the postdocs, those little things that keep the circulation moving that I never thought about before because I was always doing them. And not having a comfy chair at home.

K.C. Ogbonna: Communication is so key. Sometimes when you don't have any information to communicate, just communicating that is still valuable. I think about our emailed weekly digest and the daily student digest and the communications about COVID cases within our community and communications about PPE. All of that fell much to a few people and trying to really understand the audience and what they needed to hear and when. There was constant feedback in that process of when we were doing things well and when we weren't. I think communication was incredibly important.

I think there are things we could have done better, particularly as it relates to the COVID-case notification piece. When we think about the impact of COVID-19 on everyone, how do we help faculty, staff and students deal with grief and dying?

Katie Shedden: It was a really big time of growth for me. I suddenly had a lot more responsibility than I had before and knowledge in a specialized area that others might not have. I was able to support our school in having that knowledge and in a way it helped me to realize that I did have that knowledge. I would never have had a project this big ever if that had not have happened. I can't even imagine it.

Rucha Bond: One of the things that's come from this pandemic, just looking at it as one of the School of Pharmacy’s associate deans, is that it really shows how people value being valued. In the pandemic one of the things that became harder was for folks to recognize when people needed to be valued or where they weren't feeling valued. And some people were very undervalued.

K.C. Ogbonna: This pandemic has impacted so many. I have a number of students that lost family members. Not only they are trying to progress academically, but they're dealing with a pandemic that has literally taken loved ones. How do we help them process that, particularly in an environment where some of the normal social embraces are no longer OK? Many students grieved in isolation. I'm sure the same for faculty and staff. Thinking critically about the infrastructure and supports to handle the weight of the world is something I don't think I'll ever forget. Those conversations were challenging and hard and resources were lacking.

Serena Bonasera: It was August or September that I came back to school. That changed everything completely. I have my organization, my day-to-day life schedule and it was fine. And then obviously, for example during summer, we already knew that things might go a little bit better, so I was less scared. I told you I have always been scared, even before pandemic, about isolation or loneliness. I still am, but I am more aware that I can probably go through for some time. Maybe not years, but some time. I can handle it.

K.C. Ogbonna: I can't help but talk about the social injustices and summer events — George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the names continue. Here we are navigating through a pandemic, here we are in a professional academic program, but also the real-life aspects that subsections of our population are dealing with each and every day.

As an African-American male myself, many of them I can identify with and struggled with myself. When you mix all of that together and you think critically about what that looks like, it's not so clean. That intersection between personal, professional and advocacy — I don't think it has ever been stronger than it was in this last year.

It's made me reflect on how I want to be a part of the change, if that makes sense. Seeing what has happened with the pandemic, particularly as it relates to underserved, underrepresented populations and how it's disproportionately impacted that population, it's just given me a new lens in which I view my role and my career and where I want to give back.

Guizhi "Julian" Zhu: In the pandemic, pretty much all medicine failed, as this issue of equity. From this pandemic I've learned much more about this. You really see some striking data that some populations are impacted more serious than the others. Some of those [impacts], I would say, can be controlled — as a society we could do a better job. And so, those are some of things that I've learned. Maybe in the future my research expertise could even contribute a little bit to help address some of those issues.

Avian Goldsmith: What lessons would I carry with me? I would say this. Before the pandemic, and in my profession, in HR, you deal with guidelines, you deal with policies. You're like, "Oh, I'll give you this policy, or this, this, this, this."

The lesson that I have learned is that at the end of the day a person is still a person. Outside of my HR profession, I've learned more empathy. I've learned more understanding. I've learned that I'm resilient, and no matter how hard it gets I could press through. I really had a hard time. So I've learned empathy. I've learned resilience. I'm resourceful. Just a lot of good lessons.

Laure Ray: There were definitely some charged moments, moments where we were all scared, scared for what was coming through. I feel eternally grateful to work for a place like VCU.

Dr. Michael Rao and Dr. DiPiro are so forthcoming with kind words, words of wisdom and words of unity. I never felt like something was in jeopardy. I always felt like we were safe. I know that that can be rare. I know people who didn't get through this in that way. But the VCU community is strong, and I felt like the communication was strong. I felt reassured, and I feel lucky for that.

Katie Shedden: Everyone wants to know what is going to happen because of what we've had to go through with this whole situation. And I don't really know, I don't think anyone really knows, but I think there will be a lasting impact.

This next step is going to be a lot harder, from my perspective. We're going to have to put a lot of work into thoughtfully developing frameworks to transition— the transition back to face-to-face. What is that going to look like? What is that going to be? I don't know. I really don't think anyone knows.

Joseph T. DiPiro: It has had a big toll. We're still working our way through this. I know from conversations and other communications with our faculty and staff, there has been more physical and mental ill health than I ever recall.

K.C. Ogbonna: This pandemic environment has definitely helped me refocus on what's most important. As I think about where I want to be professionally, and as I think about how students work through our system, the education of being a pharmacist is important, but the life lessons that come with managing and navigating our curriculum is also important, if not more so.

I think about my colleagues and how the pandemic has looked different for each one of them.